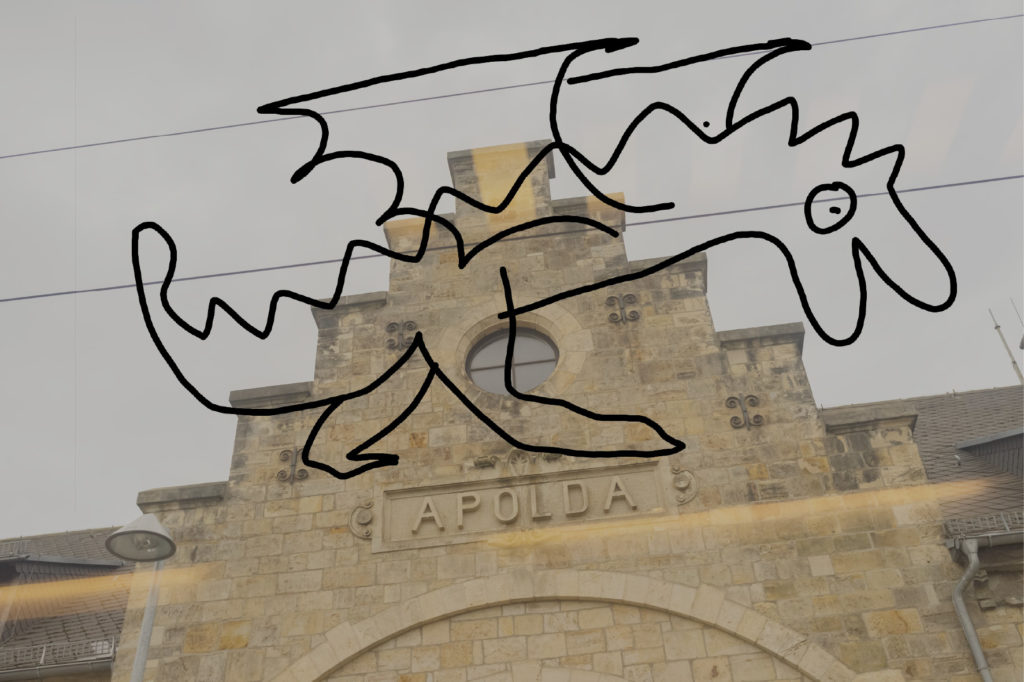

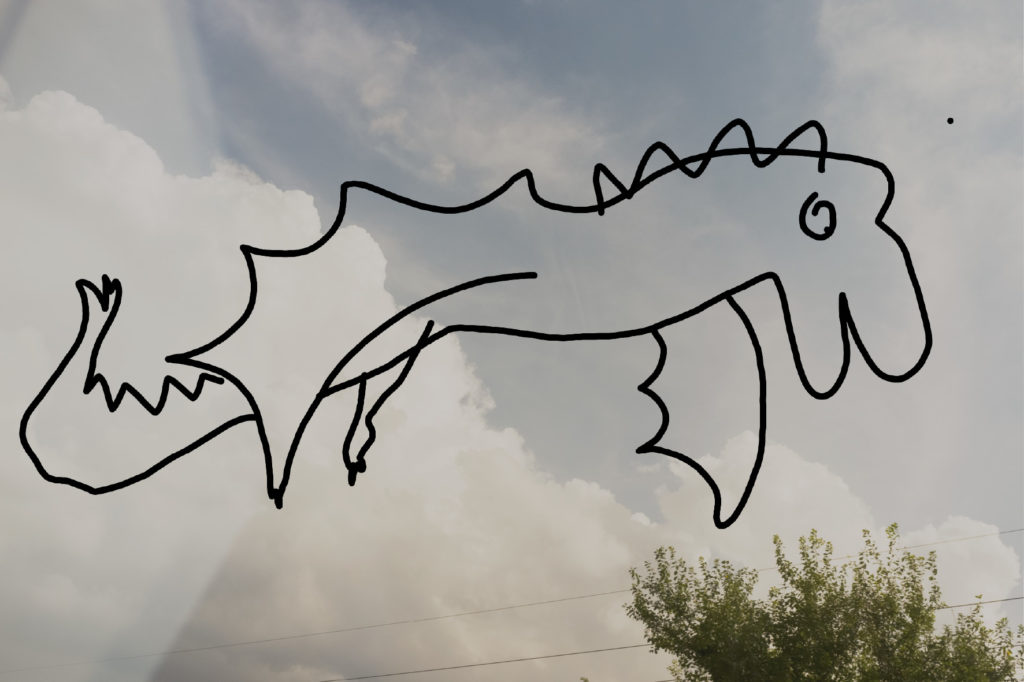

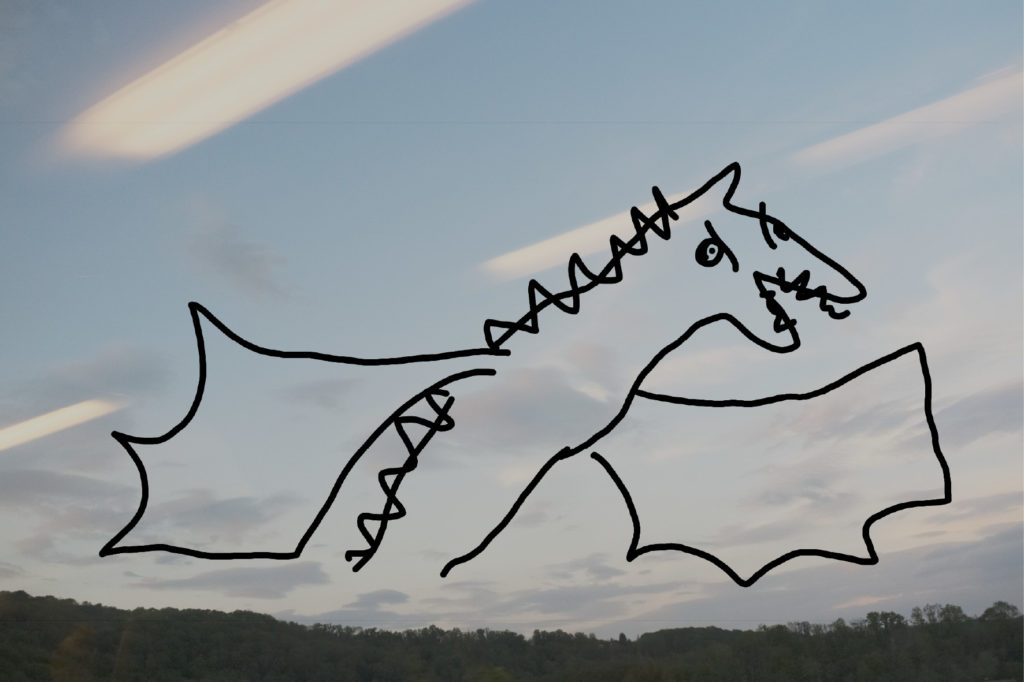

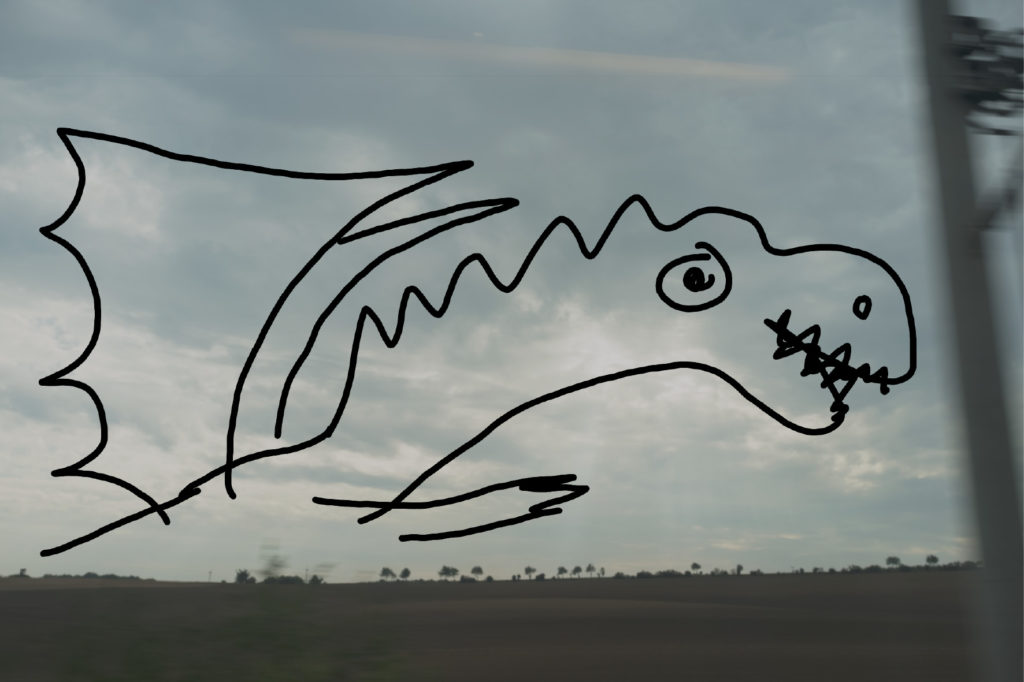

From Magdeburg, the artist takes the train back through his home region of Thuringia, reflecting on the history of anti-Semitism and right-wing violence. We observe him looking out the train window. Dragons are superimposed over pictures on his smartphone. These fantastic beasts, invisible to others, accompany him on his journey as he visualizes them with a few strokes on the display.

Jung enhances his artistic process with a stream of consciousness focused on lyrical texts, interweaving personal experiences during the train journey with memories of and reports on anti-Semitism in the area. The individual acts are not historically reconstructed, but rather outlined associatively. Alleged minor offenses and much more serious crimes combine to form a collage that allows him to approach anti-Semitism in Thuringia emotionally.

Cows pigs East Germany

Trial.

Due to Halle.

A former roommate testifies:

Whenever he was cursing

he would say Jew at the end.

But they themselves

did that, too.

And said faggot and things like that.

It was normal, in a way.

They were young.

The Kripo Live reporter

next to me bangs away at her laptop

as if she were

landing a scoop

while everyday German life is being exposed

and the trial due to Halle in Magdeburg

picks up steam.

I get on the train.

German trees.

German fields.

Everyday German life.

Pass me by.

Ten years ago, we

traveled to small towns in Thuringia

on a tour bus

and called out,

“Cows pigs East Germany.”

It didn’t change anything

about the circumstances,

even if we were right.

German culture

is also always a sausage culture.

But what if you don’t eat pork?

You’ll have a hard time

finding something to eat along the highway.

My grandpa loved bratwurst.

And when he came home from work

and didn’t eat enough at lunch,

my grandma always said:

You must have eaten a bratwurst

on the road.

My grandfather was born two days

after Hitler came to power,

and he died on a day

when I was in Buchenwald.

Jewish people?

I didn’t know any for a long time.

I don’t know many now.

A dragon appears

on the horizon

and flies along with the train,

winking at me.

Flabbergasted,

I stare open-mouthed

at my fellow travelers.

But they act as if

nothing were out of the ordinary.

I look back out the window:

fields of crops,

trees and windmills.

In the city,

backyards are home to plastic chairs

and the occasional pool.

The sun streams

through the train windows.

Brightly colored plastic chairs

in front of peeling plaster,

decked with sticky,

sweaty,

wrinkly

white skin,

gathered around

a burning grill:

Not long now before

the sausages are brown enough.

The potato salad is ready and waiting.

A German army helicopter crosses

the train’s path overhead.

A different climate outside the window

Back in the train.

More fields.

And trees.

Some are withered.

I’ve gotten used to the

dragon flying along beside me,

and the fact

that other than me,

no one in the train seems to notice.

My grandpa once

drove into a ditch

because he was watching

a red kite flying in the sky.

The sun has been shining

for three weeks straight.

In the new Germany,

the trains have A/C.

Outside,

in the climate past the window:

still a

nondescript landscape:

fields, trees, more fields.

Roads and scattered houses.

Power lines and windmills.

But castles, too.

Wonderful castles.

The wonderful Middle Ages

Wonderful barbarism.

And stuck in the wall’s cracks:

the hatred of Jews.

At Kunsthalle Erfurt:

photos of the liberation at Buchenwald.

I pass by

the New Synagogue,

firebombed by three Nazis

on Hitler’s birthday

in 2000.

On the way back,

a soldier asks me

if we know each other.

I say no.

He apologizes.

Afghanistan

A woman explains to her husband

what she just read

in the Bild-Zeitung.

She reads it

in the part of the newspaper,

he has already worked through:

“In Gera they

demolished a refrigerated warehouse,

deliberately,

they had to

throw it all away.”

We stop in Apolda.

A pig’s head

laid in front of a Jewish memorial site.

It was in the newspaper.

At the time, on September 16, 2010.

The trains are once again

full of soldiers

coming home

from their dry war

or from a real one.

At one point,

a drunken federal policeman

in uniform staggered

through the train,

drinking a mixture

out of a 1.5-liter cola bottle.

He pounded on the train door

and shouted:

“I have to get out of here.”

Told the conductress

he was a police officer.

The conductress,

barely suppressing

a smile:

“I can see that.”

His colleagues came along,

went through his bag,

and only then noticed

their comrade was steadily

drinking out of his cola bottle.

They finally led him away.

One of the travelers explained

that the drunk had spoken

about his time in Afghanistan

as a police trainer

that he wouldn’t wish it

on his worst enemy.

At the side of the road

is a backyard

with a food truck

shaped like a bratwurst,

apparently left for scrap.

At the main train station in Erfurt,

a blind man

gets out with us.

The ticket collector asks

if he is looking for someone.

The blind man says:

“Yes,

a woman

in a colorful dress.”

Dentist

I’m sitting at the dentist.

We celebrated my

grandma’s birthday

at the nursing home yesterday.

My grandpa died last year.

My dentist is

the best-looking dentist in the world,

at least judging by the waiting room.

Therefore, I still make

a special trip from Leipzig to Jena,

to see my dentist

and visit

my family.

The dentist is done

and because he likes me,

he didn’t drill.

I’m sitting at the Jena West train station.

Across from the platform is a plaque:

“In memory of our

fellow Jena residents,

the racially persecuted

Jews, Roma and Sinti

who were deported

from here to

the fascist death camps.”

How must someone feel

who has to go to work

through this train station

every day,

someone whose family

the Nazis destroyed.

On Facebook, a photo of

an automobile scrapyard pops up:

“Dirty Jew” is scrawled

across the rear windshield

on one of the wrecked cars.

A poster for the

Marc Chagall exhibition

in Apolda

hangs at the Jena-Göschwitz train station.

I get on the train for Gera,

for the Otto Dix exhibition.

Was Otto Dix an anti-Semite, actually?

He was in the war.

But only the first one.

I’m looking forward to his work.

The sun is shining.

A guy sitting near me asks me

if there was a fire or something,

apparently meaning

a non-white person

sitting two rows away.

A little crestfallen,

he falls silent

when I don’t laugh

and pull my latop right

in front of his face.

When we stop in Stadtroda,

he collects the pieces

of his face

and gets off.

I’ve arrived in Gera.

I go to a bakery and

pick up a ham and cheese pretzel for € 1.50,

which feels like it weighs one kilo.

In front of me, a healthy-looking

young man waves around a piece of paper

saying

he doesn’t have to wear a mask.

The Otto Dix exhibition is wonderful.

The train runs along the Elster River.

The dragon floats along in it.

Why fly

when you

can let German water

carry you.

We pass by Zeitz:

33 percent of voters here voted AfD.

On a small hill at the Posa monastery,

a couple of people raise the flag.

For an open society.

When I staged an intervention

in a vacant butcher’s shop there,

a couple of young,

dynamic people got out,

the makers

of a feminist erotic magazine,

and cried out to the people:

“Wow, awesome!

How fucked up is that?”

German

At the Mühlhausen train station,

the roofs of the bus shelters are rusting.

The uniform train station design

used by Deutsche Bahn

has already taken hold.

On the old station building,

a cartoon figure

pisses on an Israeli flag.

To the left

is a picture of a waving swastika flag.

They seem

to be around in these parts, too,

the lone perpetrators,

driven by the

brown rust of history,

still not cleared away,

clapped on the shoulder

by their relatives.

“We were young once, too.”

And anyway,

just because someone

covered something once with grafitti

doesn’t mean

the whole town…

“Right-wing extremists?

Listen,

those are our kids.”

An older lady sits down

in the four-person spot next to me.

She points to my stuff,

FAZ newspaper,

Süddeutsche Zeitung,

laptop,

backpack

and bag,

and asks:

“Is all that yours?”

“Yes,” I say.

“Do you want to talk about it?” I ask.

“No,” she says,

and pulls out all

her own stuff accusingly

and spreads it

on the three seats around her,

huffing in

exasperation.

But she’s right,

I should tidy up

my desk.

I almost feel sorry for her,

trapped in her

rusty thoughts.

But as long as she’s only mad

at my stuff,

that’s fine with me.

Although the question remains:

What is the nature of tidiness?

Toward the end,

I feel sympathetic toward her.

We’re all punk rock somewhere,

whether it’s me in my shirt

with littered space

or her with her sense of order

and shoes on the seat.

De-Jewing Institute

I’m sitting in the Martin Luther

on the way to Eisenach.

That’s the name of this high-speed train.

Naming a train in Germany

for an anti-Semite:

classic.

“Come on, back then

everyone was an anti-Semite,

even the Jews.”

Who says that?

The dragon

flying along by the train

winks at me again.

Over there, the bell tower in Weimar;

Buchenwald.

And here on the train,

the grandchildren of those who did it.

Now we start climbing the hill

to the former De-Jewing Institute.

It’s actually called the Wartburg.

Founded in 1939

by the Protestant church.

I read a report in the paper

about the Waldklinik Medical Center in Eisenberg.

They want to offer

kosher food now.

I’m looking forward to seeing the Wartburg.

My grandfather had

a model of the Wartburg in his office.

He had made it himself.

That was before the office

became the TV room.

“I want to die

like he did.”

We stood around his deathbed,

all of the remaining family members.

Not dying alone:

the final privilege.

I can still see the bell tower

of Buchenwald

on the horizon.

The train stops in Erfurt.

Passengers get on

and look for their reserved seats.

Martin Luther spits me

out in Eisenach.

20 minutes before the

Wartburg shuttle comes.

In downtown Eisenach,

a blind woman wanders around the street

between honking cars,

at the feet of Martin Luther’s statue.

Behind the memorial,

the dragon traces circles in the sky.

I help the blind woman get off the street,

and she attacks me:

“This isn’t where I wanted to go at all.”

Back at the bus stop,

the shuttle pulls up,

driven by a beaming bus driver

with a German baseball cap on his bald head.

The weather is pleasantly mild,

with a slight breeze from the right.

Three blocks along,

a knight

fights with

a dragon,

covered with verdigris.

For you.

For here.

The Eisenach CDU advertises.

I sit way up

in the former De-Jewing Institute,

at a café,

surrounded by tourists

who are just visiting the castle

to catch a glimpse

of the good old days

in the Middle Ages.

I order a double espresso

and water.

With tip, it comes to 10 euro.

Typing on my laptop,

I imagine

how Martin Luther

wrote his hate-filled tirades against the Jews

here, using a ripped-out goose feather,

and how later,

a bunch of Protestants

sat here at the very same table

and founded the Institute for the De-Jewing of Christianity.

My laptop is the new quill,

no longer ripped from an animal’s body,

no, its production conditions now

cut a swath of destruction

across the entire planet.

All a single cultural history

of barbarism,

to which we refer here

so romantically.

It’s 12:46.

Lunch is officially over,

and the restaurant is deserted.

Germans are

reliable in every way.

On the way to the train station,

I pass

the Wartburgsparkasse bank.

It’s the one the two Uwes

robbed back then,

before they blew

themselves up with a pump-action gun.

“All that is Germany,”

I hear in my head,

a song sung by Die Prinzen

as they stand in the Chancellor’s office

and make a fuss for Angela Merkel.

The faces of the people

on the streets

are neither sad nor happy.

Instead, they are striking

for their captivating

expressionlessness.

As if they were all

just doing their duty.

Going to work.

Shopping.

Eating.

Sleeping.

Cemetery

I sit in the front window of a bakery,

eating a sourdough roll with chia seeds

and drinking an espresso.

The lady baker

gave me a pat of butter on the house.

“It tastes so dry otherwise,”

she says.

I look out the window.

A man with a yellow armband walks by.

One of the three sewn-on points

looks about to fall off;

it’s hanging by a thread.

The roll tastes good.

Later, I drive through Gotha.

You can’t go to the Jewish cemetery there

unless you register in advance

with the city authorities;

in 2008, two men hung a pig’s head on the cemetery gate.

At the neighboring table, a mother

and her two sons,

around 10 years old,

discuss whether the salted almonds

don’t taste salty enough

for salted almonds.

Outside is an idyllic little house

with a little garden.

The sun comes out.

The sky is blue.

CoronaCentrifuge

I take the CoronaCentrifuge

from Erfurt to Jena.

Halfway there,

the bell tower

reappears.

All around me,

beads of sweat

roll off foreheads,

get caught in masks,

or drip to the floor,

the last drops of sweat

the September sun

will wring out of us travelers this year.

Everyone is wearing a mask.

And no one babbles

about what they read the night before

in some

WhatsApp or Telegram group

by coronavirus conspiracy theorist Hildmann or his ilk.

And no one

talks openly

about those

who supposedly

invented the coronavirus.

And no one wishes

it on anyone else.

If I don’t catch COVID-19,

it was almost a good train trip

in Germany,

other than the fact that it was hot,

aside from the bell tower,

which I overlooked

so many times over the years,

the more I passed it,

when I still lived

among the dragons and the castles.

In the Mühltal valley, on the way to Jena, the dragon keeps getting stuck in the trees and falls behind.

Jewish Jena

I’m sitting in the DB lounge

and working my way through

the coffee assortment.

Ice cream season is over.

The freezer plug is pointedly sitting on top of the freezer.

My train to Jena

is coming in 50 minutes.

It will catapult me back

home.

Back to

where a terrorist group

was radicalized:

Uwe, Uwe, Beate and friends.

Back to

where the NSU’s right-wing terrorism

started building its network across the whole country.

“Jena, do you have any Jews?”

I’d like to scream at my doll-sized little city,

even as I sit here in the DB lounge

over free coffee

with my special passenger status.

A thin woman about my age pours herself a Diet Coke.

I HAVE NEVER SEEN

A THIN PERSON

DRINKING DIET COKE,

shouts Donald Trump in my head.

The DB lounge employees are dealing with a bee

and ask her to make a detour.

The police once found

one of the Uwe’s

fingerprint

on a doll with a Star of David on it

hung from a freeway overpass.

At that point, he was convicted

because his alibi could not be verified.

They didn’t even know

who won the PlayStation game.

In the second instance, Uwe was

acquitted,

because

Uwe,

Uwe,

Beate, and Ralf suddenly

all remembered everything exactly:

Ralf won at PlayStation,

because Uwe

was playing it for the first time

and then they radicalized themselves

after that.

When the Erfurt soccer team

played Jena in Jena,

the Erfurt fans

were known to chant:

“Jewish Jena.”

All just individual screamers, of course.

Individual offenders.

Well, Erfurt,

where are Jena’s Jews now?

I leave the German National Railway employees

alone to deal with their bee issue.

The train enters the station.

Off we go, heading home.

Off to the city

where the optical industry

designs the rifle scope

so people all over the world can blow off each other’s heads.

Did the pump-action gun that Uwe and Uwe

used to blow off their heads

have a lens from Jena, too?

Pump-action guns

don’t have a scope,

murmurs the dragon,

who is back,

flying along by the train.

Brown stripes

Outside, the landscape

passes by in brown stripes.

In the winter the fields are black,

seldom white.

In spring, yellow rapeseed fields.

In summer, red, burning trees.

In autumn it’s all brown again.

Black.

Gold.

Red.

Brown.

Next stop, Magdeburg.

Where the Halle

attacker is still on trial,

and analog bureaucrats try to understand the Internet.

At the Halle train station,

a giant pin-up

on a bordello firewall

looms over the roofs.

The train passes

two former

Russian barracks rotting away.

The Russians are gone,

and the state is using properties like these

for refugees less and less.

The concrete slab buildings look like the ones

from Freienbessingen,

a refugee camp from the 2000s

where I went with my cows-pigs-East Germany friends.

I came back with pictures:

broken sinks,

moldy wallpaper

and disconnected heaters,

photos for a campaign

to close the camp.

At least there, taking the bus

was worthwhile.

The camp was in fact

closed at some point.

But maybe only

because the government

found a cheaper per capita accommodation

somewhere else.

There was a fire

at the Moria camp a couple weeks ago,

and everyone said:

We told you so.

No one likes a wise guy.

Europe is blushing

as if it had been caught taking a shit.

Even Merkel is supposed to have said:

We knew it.

We’re all to blame,

and it doesn’t change anything

if we go to a solidarity protest

in the afternoon

before we stream

the planet to its knees

in the evening.

Whataboutism?

Welcome to hell.

It’s become cold.

The A/C is turned on inside the train

even though it’s only 10 degrees Celsius outside.

The sky is cloudy.

Here and there,

trees are already turning yellow.

Migratory birds gather

on the power lines,

ready to set off for the Mediterranean

and beyond,

while below them,

a few brown cows

await the winter.

What impact

will climate change

have on the migrating birds?

When will the first ones decide

to stop denying climate change

and blame the Jews

instead?

When the coronavirus pandemic

reached the white man,

it took just the blink of an eye.

The train compartment reeks

of perfume.

Outside,

matchbox cars

drive along

drawn-out rural roads.

Oh,

if only the rest of the world

would just stop

wanting to have

our privileges.

RV: Bang

A solitary RV

is parked on a dirt road ,

with a grill in front.

Two men

and a woman

loll in folding chairs.

The sausages on the grill

are charred.

The men’s heads

hang back at an unnatural angle.

The woman drinks sparkling wine

out of the bottle.

Next to the RV

lies a scarecrow

with a Star of David patch sewn on it.

A couple of crows

pull straw out of it.

The RV explodes.

A black car

labeled as belonging to

German domestic intelligence

drives away.

I wake up.

Oh, if only it were so simple.

The happy faces

in the home improvement store

near the train platform

are faded.

A child is crying

again in the neighboring compartment.

The federal criminal authorities are

still asking for clues from the public.

The NSU investigations

aren’t over.

But shredded files

are shredded files.

A screaming child

makes the eyeballs of some of my

fellow travelers’

pop out in their eye sockets.

The dragon?

Where’s the dragon?

Woodchip apartment

What am

I looking for here, anyway?

On the trail

of people hostile to Jews.

Is it a perverse German idea of

how to spend the summer?

To stick your finger in the wound

and from time to time

make some melancholy joke

suggested

from the sheer absurdity

of the circumstances.

The train stops somewhere

in the East German nirvana.

Around the former train station

are skinheads in under shirts.

They bought themselves a former

Holocaust shuttle

so they could live in it.

One of these pigs

has written

“Grandpa was all right”

in permanent marker on his under shirt.

The train starts moving.

I throw open the window and call out:

“Was your grandpa in the Resistance, too?”

As the clown starts to rage,

we leave the little town.

My grandfather wasn’t

in the Resistance at all.

I’m disgusted

at my own self-righteousness.

Is it enough

to throw words

in Nazis’ faces?

The sun

goes down.

A light is burning in the

Rudelsburg castle.

Home

at my apartment

in Connewitz

Woodchip wallpaper.

The walls as white

as an east German town,

or Connewitz itself.

The floor, light brown;

click laminate.